2006

2018; 2017; 2016; 2015; 2014; 2013; 2012; 2011; 2010; 2009; 2008; 2007; 2006; 2005; 2004; 2003; 2002; 2001; 2000; 1999

Main Gallery

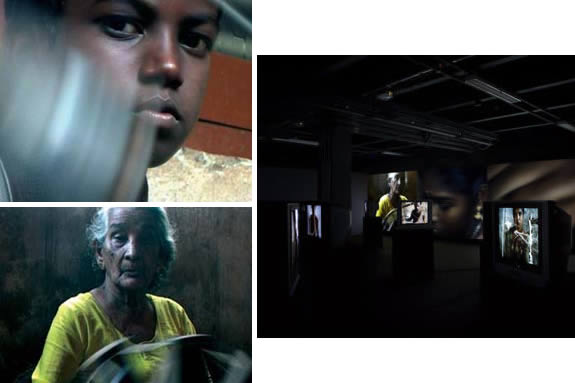

Tania Mouraud

La Fabrique

November 4 – December 17, 2006

www.tania-mouraud.net/entree_taniamouraud.htm

La Fabrique is the extension of Tania Mouraud’s videographic work but it is also the creation of a new open space. Indeed, La Fabrique completes a polyptych of videos by introducing for the first time the human figure into a place of fabrication. In Sightseeing, Le Verger (The Orchard), Du Pain et des jeux (Bread and Games), Or donc (Gold Now), the individual is projected into the foreground by his/her absence. The individual’s condition is revealed by the periphery or surroundings, by the objects and spaces.

La Fabrique was created for the international exhibition lille3000. The videos, shot in Kerala, India, show male and female textile workers in their work locations and at their work stations.

The number of workshops, the diversity and the richness of the actors who give life to the weaving machines, led Mouraud to “shoot/edit”. This was necessary to preserve the spontaneity of the action, of the sound and visual rhythms, while eliminating the cliches of video reporting.

The installation chosen by Mouraud for lille3000 consists of 29 videos, 8 to 16 minutes each, shown on 25 TVs and four wall projections. [For the site at lille3000] the 25 televisions are set upon stands scattered around the space; each set with its base is to be viewed as a physical entity. What is at stake is to constantly link the viewer with the weavers, to create a complicity with them by the interplay of nonaccusatory gazes inviting you to share a common space. The wall projections [dis]place this relationship and send us back to our reality and, as Giorgio Agamben wrote, “…such as a precious veil of Maya which one will never ever be able to grasp concretely, but only through the reflected image in the magic mirror of one’s own taste.”

Jorge Luis Borges wrote, “He does not use the word meaning time. How can you explain this voluntary omission?” In La Fabrique, time is not left out but rather suggested by the rhythm and the repetitive gestures which the sound of the mechanical clacking of the loom punctuates at regular intervals. The sound that indicates the end of one process and the beginning of another does not fade away here; it does not illustrate anything. It marks the presence of the loom, carries temporality, and makes the link between the entire installation in motion and the viewer. Sound in La Fabriqueintervenes like a text interpreted by different actors; here I will borrow the reply of Kluge to Muller: “- Ah, as a sort of factory in which the texts would continually be repeated…?” In La Fabrique, there are no anecdotes to tell or to discover. We are confronted with patterns of reality, this reality which is so close to us: Kerala is in Lille and vice versa. With the development of new technologies, the third millennium penetrates spaces, abolishes frontiers, reduces time to its smallest measure. This allows Mouraud to assert the combination sound-images-space-time in order to displace the viewpoint of the viewer in order to lead him/her to discovery and to knowledge. But, as Georges Didi-Huberman has written, “To know, one must imagine. To know, one must imagine oneself.”

Those are the issues that Tania Mouraud develops in La Fabrique, while giving it a poetic dimension that I would link to a quote from Beaudelaire: “Poetry is that which is the most real, that which is completely true, only in another world.”

Pierre Petit

June 2006

Pierre Petit is an artist and professor at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Tourcoing, France.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Project Room Gallery

Laurie Hassold

Exorb

November 4 – December 18, 2006

Blood Is Sicker Than Water: The Art of Laurie Hassold

by Tyler Stallings

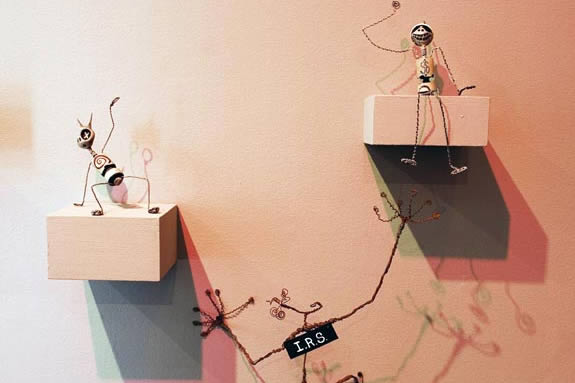

Laurie Hassold’s Strange Attractor series suggests the results from an excavation by a paleontologist in the future. Bones, combs, syringe tips, and wires are only a sampling of the components that compose her innovative and futuristic skeletal structures. Their outward appearance of muscle and tissue is mysterious, but whatever the epidermis, it is clear that they are a combination of the organic and the artificial.

On closer inspection, it becomes apparent that they are not bones foretelling the unimaginable, like ancient Chinese oracle bones used for divination. Rather, they are intricate sculptures made from Apoxie Clay and objects found in the home. They are a cross between the handmade aesthetics of a Michaels crafts store and Dr. Frankenstein’s laboratory.

Frankenstein’s monster was literature’s first cyborg in which man-made technology brought to life a heavily sutured creature, one that was composed from disparate human body parts. It was an early-nineteenth-century story that could be read as a morality tale about the disregard for human life after the rise of the Industrial Revolution, the over-reaching of this new modern man, and the consequences of his irresponsible use of new technologies.

But Hassold’s work is less about the co-evolution of humans and their technology, and more about the most enduring of philosophical conundrums in Western society: the apparent separation between mind and body. Hassold is fascinated with bringing the insides of the body to the outside in order to have a better understanding of our mental states. Her lacy, bold, ornamental sculptures are a sort of baroque showmanship that aims to expose our anonymous interiors.

Several years ago, Hassold created two performances that, in retrospect, shed significant light on her process. In The Impossibility of Achieving Pain Without Suffering (2000), performed in a vacant gallery in Santa Ana, California, she was confined in a big white box that was brightly lit with surveillance lamps and a surveillance camera mounted in an upper corner. People outside the cube could observe her on a monitor. Hassold had also pre-arranged for a male stripper to mingle with the crowd, pushing a gurney that sported a blood bag from which he dispensed red wine to viewers.

For two hours, Hassold stuck her fingers with a lancet that diabetics use to test their blood. With the blood flowing she drew bloody hearts on the walls. As a testament to her endurance, she said that she could complete three hearts for every prick of the lancet–but hundreds of hearts meant hundreds of tiny punctures in her fingers.

A second performance, Interruption of a Closed System (Random Symmetry), followed in 2003 and was performed as a one-hour action at Crazy Space in Santa Monica. In this work, Hassold stood at an overhead projector, pricked her finger, squirted blood from her finger onto transparent paper, folded it over, and created a Rorschach inkblot-type drawing that was projected onto the opposite wall. The drawing went from being three inches on the paper to being six feet on the projection. Afterward, Hassold was joined by a registered nurse who withdrew several vials of blood from her arm. Hassold then emptied the vials of blood into a pan and proceeded to use it like paint, tracing over the projected and enlarged image of the original blood drawing.

In these performances, Hassold connects her acts with early human rituals and their variations including present-day incarnations. For example, among the Germanic tribes (such as the Anglo-Saxons and the Vikings), blood was used during sacrifices, called Blots. The blood was considered to have the power of its victim, which inspired conquerors to sprinkle their blood on walls, on statues of gods, and on themselves. This act of sprinkling blood was called bleodsian in Old English, which was borrowed by the Roman Catholic Church, becoming to bless.

In an art-historical context, Hassold’s performances follow on the steps of the Viennese Actionists, such as Hermann Nitsch (b. 1938). In the 1950s, Nitsch conceived of the Theatre of Orgies and Mysteries, staging nearly 100 ritualistic performances, which often included staged crucifixions and animal slaughter. But a much more direct influence for Hassold is Marina Abramovic (b. 1946), especially her body-based Rhythm performances of the 1970s. Hassold has said, “It was through her that I first became aware of the mind/body duality issues present in my own work.”[i] For example, in the 1973 performance Rhythm 10, Abramovic’ played a Russian game in which she jabbed a knife between her splayed fingers. Each time that a knife missed the table and hit her finger, she would pick up a new knife and begin again. She audiotaped herself going through this process, and after she cut herself twenty times, she listened to the tape and tried to repeat her movements, including the accidental wounds. Through this ritual, Abramovic’ explored issues of time, the extremes to which she could submit her body, and the resulting altered states of consciousness created through repetitive acts. In other words, could the body be pushed beyond one’s assumed limitations?

Through her art, Hassold, like Mary Shelley with her 1818 novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, is exploring how we as humans define ourselves in a heavily mediated world. One can argue that we have been cyborgs ever since we began to use tools, as our identity as human has become inseparable from our use of tools. In Hassold’s case, the allegory, then, is less a warning about man’s dependence on technology, since that has been the case always, and more a question of how our identity is affected by our bodies.

One cannot help but think that Hassold’s early emphasis on blood is a commentary on the world since the advent of AIDS. Certainly, various body fluids can transmit HIV, but blood is its poster child. It elicits in our minds the phrase, “blood is thicker than water,” which implies that familial relations override any petty intolerance, but now, with a horrible twist of irony, one might say, “blood is sicker than water.”

In such a world, we have seen several body horror films, especially those by director David Cronenberg, in which our own body becomes our worst enemy. In films such as The Fly (1986), Dead Ringers (1988), and eXistenZ (1999), the body is invaded and violated, and undergoes disturbingly grotesque changes. In other words, one’s own body becomes the disease that the mind must kill.

However, another philosophical question that these films deal with to some degree is the idea of purity. A part of the horror is that the human body as we know it is being transformed into something else, such as a hybrid human/fly, or an organic video game portal. But just as we now acknowledge that our psychological identities are ever changing, that is, there is no core self, so now perhaps will we accept the possibility of our physical selves as ever changing.

In Strange Attractors, Hassold suggests that these bodies are the future fossils of creatures who have adapted to an evolution of impurity. It is as though they survived by incorporating what will be at hand, whether it be a hair clip that will become mandibles, or metal wire that will become whiskers.

The use of industrial materials in an organic fashion alludes not only to the literary and cinematic cyborg, but also to the works of several artists such as Eva Hesse’s (1936-1970) use of latex, fiberglass, and plastics; to Lee Bontecou’s (b. 1931) drawings and sculptures that suggest the intersections of tree hollows, body orifices, armor plating, and insect bodies; and to the younger, Korean artist Lee Bul’s (b. 1964) hand-cut-polyurethane cyborgian sculptures. In another sense, Hassold’s work is a cross between Hesse and the Swiss artist, H.R. Geiger, whose psychosexual paintings of interconnected bodies and machines inspired the skeletal, aggressive extraterrestrial in the film Alien (1979).

Hassold has subtitled several of the works after flowers, such as Cyborchid, Lily, Tuber, and Spider Lily. This points to her fascination with things that are both attractive and repulsive. In the case of her sculptures, their ornamental nature makes them aesthetically attractive, but on closer inspection they are often imbedded with pointy objects, as if they were stingers, ready to subdue a prey that has been drawn in by the beauty.

The ornamental quality of the Strange Attractor series and the components that create the Process Wall point to drawing as one of Hassold’s major sources of inspiration. Elements in the Process Wall include drawings made with insect parts (the insect carcasses were courtesy of her cat), blood drawings, pencil drawings, tests for sculptures, and what appear to be fragments of stretched lace but are in fact pieces of silk whose designs have been drawn/burned with lit cigarettes.

For Hassold, the fact that much of her output has the appearance of being inspired by the symmetry and ambivalence of Rorschach inkblots is less an allusion to the psychological test and more as a way to use symmetry as a means to suggest that there is an order to the chaos. Her method is more akin to automatic drawing.

Automatic drawing was developed by surrealists such as Andre Masson, Joan Miro, Jean Arp, and Andre Breton in the first half of the twentieth century, as a means of expressing the subconscious. In automatic drawing, the hand is allowed to move randomly across the paper. In applying chance and accident to mark-making, drawing is to a large extent freed from rational control. Hence the drawing produced may be attributed in part to the subconscious and may reveal something of the psyche, which would otherwise be repressed. This desire to release oneself of rational control, yet doing so through the movement of one’s hand, is another way of exploring the mind/body connection/split. It emphasizes the subjective as the path toward truth.

The Process Wall is important to understanding Hassold’s oeuvre. The use of pattern, of symmetry, the direct reference to lace, and its presentation as a kind of Hess/Geiger-inspired biomechanical wallpaper, all point to the domestic environment as being very important to her. Lace as a motif is perhaps the most important aspect to recognize in her work because of its being a network made from a single strand, emphasizing the interconnectedness of all things.

In fact, Hassold has said that the inspiration for the cigarette-burned lace pieces was her imagining a hybrid person making them who would be a cross between the writers Charles Bukowski (1920-1994) and Emily Dickinson (1830-1886). For Hassold, Bukowski is the chain-smoking, chain-drinking, sloppy bachelor writing about an L.A. that crossed the little street corner of his life, and Dickinson was a little-published nineteenth-century poet whose work had great influence after her death. She lived a reclusive life in Amherst, Massachusetts. But despite being a century apart, both of these poets focused on the little moments of daily life and the small dramas within their local worlds.

For Hassold, the cigarette-burned lace also connects the work directly back to the body. In a very real sense, she exchanges part of her life, through the ill effects of smoking, to make the delicate lace. Again, this view brings us back to Eva Hesse, whose early death from a brain tumor is reported to have been the result of her use of toxic chemicals such as resin to make her work.

This interest in the domestic brings us to Hassold’s most recent work, O2dek: Hair from the Family Plan. It is an installation that was inspired by the Franz Kafka (1883-1924) story The Cares of a Family Man. Hassold has made her own version of Kafka’s unusual creature, Odradek. At the end of the story, the anonymous narrator asks himself, “Am I to suppose, then, that he will always be rolling down the stairs…right before the feet of my children, and my children’s children?” Kafka’s narrator is a man coming to terms with his mortality and also with the responsibilities of family life. The story is about the limitations of the physical body and of domestic life. In a recent interview, Hassold said that, for her, this story and her own work inspired by it are about “family legacy as a trap.” Her installation attempts to visualize this trap.

Just as Kafka’s narrator contemplates what will survive him, that is, what he will leave to the world and to his family–hoping that Odradek will not be the only thing–so does Hassold contemplate through her fantastical work what it is that will survive the human species after their extinction. By suggesting that her sculptures are the fossils of the future-living, which combine organic elements and industrial artifacts, Hassold’s works become allegories for humankind’s dichotomous nature–we can create beauty, but we can also destroy it, and much more.

Tyler Stallings is the chief curator at Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach, California.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Education Room

IN APPROPRIATE

Artwork by Jeff Gillette

October 7 – October 28, 2006

Also Featuring the ORANGE COUNTY premiere of: THE SUGAR ON TOP A film by Otis Link, winner of the SILVERLAKE ARTIST OF THE YEAR award One Night only!!!

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Main Gallery

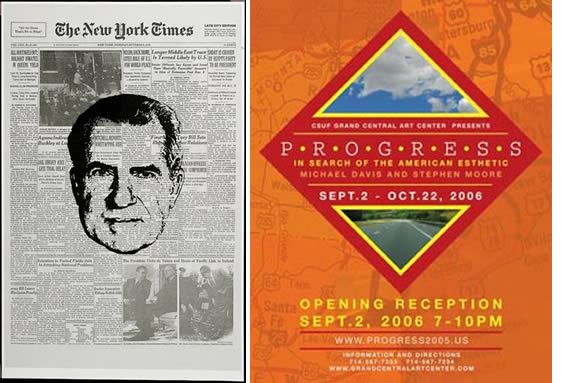

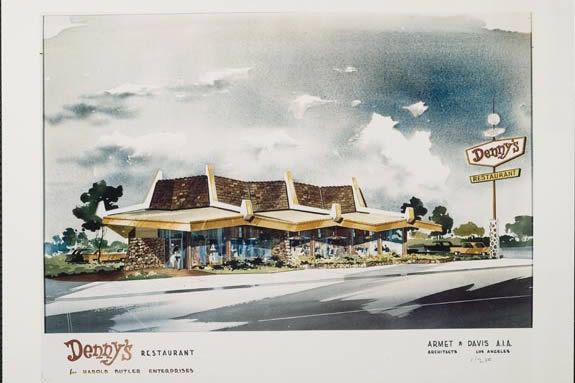

PROGRESS: In Search of the American Esthetic

September 2 – October 22, 2006

PROGRESS: In Search of the American Esthetic is an exhibition that features photographs, video projections, audio and ephemera documenting artists Michael Davis and Stephen Moore’s cross-country trip by car from California to New York in 1970 and their subsequent trip traveling the same route in reversing, form New York to California, in 2005.

It was California in the late 60’s. Pop and Minimal dominated the art scene. During one tediously long seminar, Cal State Fullerton art students Davis and Moore decided that it was time to experience what they were theorizing, not secondhand, but in the flesh. They determined to see cutting-edge artwork and meet as many artists, curators, and gallery owners as possible. In addition, they would chronicle their travel experience via film and conceptual artworks.

What began as a graduate research project evolved into a 3,140 mile road trip documenting the icons and sounds of roadside America in 1970; a mixed-media observation that served as prolog to the destination itself.

According to Davis: Traversing America, we would witness a changing and transformed landscape, a representation of progress.

If progress is the notion that society moves forward, advancing toward a more desirable form, it seemed to us in 1970 that this concept was in essence paradoxical. These contradictions framed our viewpoint in the creation of a time-lapse film and the compilation of hundreds of images shot on the road.

PROGRESS 2005 is a mirror image of that drive. Departing from the Big Apple, Davis and Moore traced the original route, closing the loop that they began 35 years ago. Along the way, they attempted to translate the jargon, political and visual, that has since proliferated along the nation’s highways.

Their documentation tracks the globalization of the American economy, and its impact on the landscape. Present-day technology replaced film and hand-written journals with digital video and web updates. At the end of their journey, they perused the West Coast art scene.

They journeyed not so much to a destination but toward a point of view, asking: What has changed about roadside America in the years since the original trip? And how does that affect the way they–and other travelers–see the country?

They encountered the transition from homespun signage to corporate logo, from unique abode to mass housing, and confronted the transformation of not just the American landscape but the American Dream as well.

The artists are both Alumni of California State University Fullerton. Michael Davis is based in San Pedro, California and Stephen Moore is based in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania. Subsequent to the exhibition, Grand Central Press will also release a publication documenting the project.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Project Room Gallery

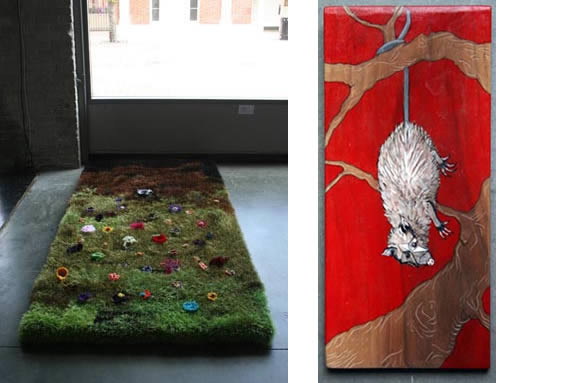

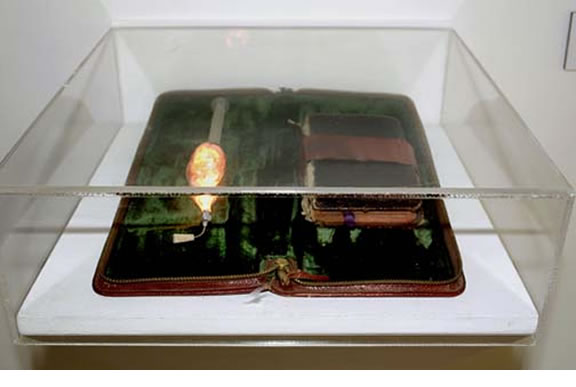

Take Off Your Coat. Stay Awhile.

September 2 – October 22, 2006

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Education Room

FM Rides Alone

Lowrider Art and Culture

September 2 – October 1, 2006

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Main Gallery

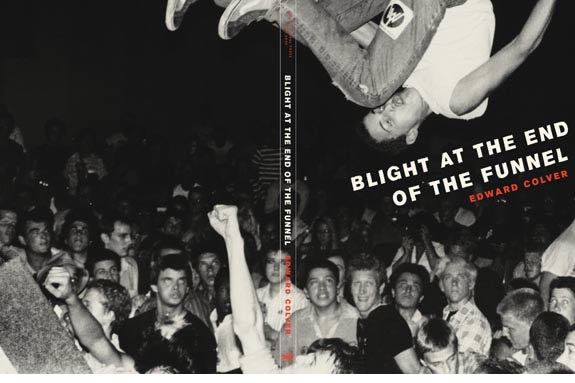

Blight at the End of the Funnel

Edward Colver

July 1 – August 20, 2006

Edward Colver’s exhibition and book titled, Blight at the End of the Funnel, are epic explorations. The 200-page book and the exhibition examine the artist’s creative life from his many years documenting the punk music scene in Southern California, to his edgy, witty, poignant assemblages. The exhibition will feature 20 selected photographs and 15 assemblage works in the Grand Central Main Gallery and, in the Grand Central Project Room, Colver will assemble an original installation. The 200-page book, co-published by Last Gasp Press (San Francisco) and Grand Central Press (Santa Ana), will be printed in both hard and soft cover editions and feature more than 300 black-and-white and color images. Mick Farren, Mat Gleason, Larry Reid, and Jocko Weyland contributed essays for the book.

During the opening reception on Saturday, July 1, 2006, Colver will sign books from 6-7:30 p.m. In conjunction with the exhibition, a special admission-free concert will take place on the Artists Village promenade from 6-10 p.m. featuring the band Flipper and surprise guests. This project was sponsored by Quiksilver Edition. Art Direction and Design by Ryan DiDonato and Andrea Harris, Editor Sue Henger, Original Layout Concepts by Brent Martin. Printed by Prolong Press, Ltd. Hong Kong.

As Mat Gleason the editor of the Los Angeles-based magazine Coagula wrote in his essay for the book:

Edward has pursued his own abyss-nested muse with no regard to the whims of taste or convention. Edward’s artistic oeuvre carries the authenticity of Dada, European art’s most radical movement, and the street credibility of the early L.A. punk scene, American music’s edgiest moment. To paraphrase the Sex Pistols, “He means it, man.”

Born June 17, 1949, in Pomona, California, Edward Curtiss Colver is a third-generation Southern Californian. Colver is largely a self-taught artist. Influenced by dada and surrealism (he admired Dali’s personality), he was most impressed in his early years by the art of Southern California native, Edward Kienholz. In the late 1960’s, Colver’s perspective on life and art was changed dramatically by his exposure to composers such as Edgar Varese, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Krzysztof Penderecki, and, most notably, John Cage.

Three months after he began taking photographs, Colver had his first photo published, an image of performance artist Johanna Went, featured in BAM magazine. He has shot for dozens of record labels including EMI, Capitol, and Geffen and his photographs have been featured on more than 300 album covers.

Colver has not watched TV since 1979. He currently lives in a 1911 Craftsman house in Los Angeles with his wife Lani.

Link to online version of OC Weekly article by Theo Douglas: N/A

Shot in the Dark, by Larry Reid. Juxtapoz magazine

Back From the Pit, by Brendan Mullen.

Artillery Magazine, September 2006

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Education Room

I Heart Painting

July 1 – August 27, 2006

A series of works commenting on movements from Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Main Gallery

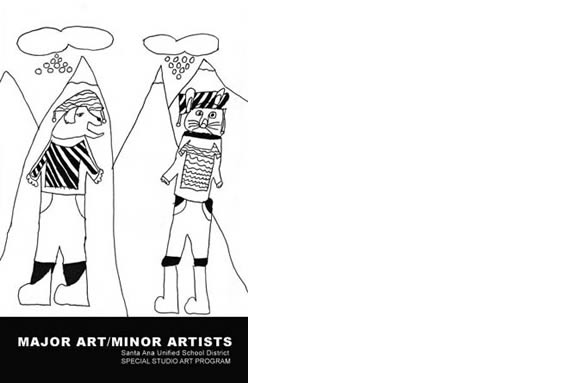

Major Art /Minor Artists 2006

Santa Ana Unified School District

June 3 – June 18, 2006

The annual presentation of Santa Ana children’s artwork and the young ,creative spirit SAUSD’s SPECIAL STUDIO art program. This year’s young artists (grades 4 and 5) are from Garfield, Hoover, Washington, and Wilson Elementary Schools. Students work with artists Cheryl Michelon and Helen Seigel weekly to create original works inspired by eclectic sources including art, literature, science, mathematics… essentially art about life. On exhibit: drawing, painting, collage, printmaking, and mixed media works.

Contact for more information about the exhibit:

SAUSD SPECIAL STUDIO art program

Artists-in-the-Schools: Cheryl Michelon & Helen Seigel

714.558.5541

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Project Room Gallery

Oil Elastic-World of Plastic

A Degeneration-Regeneration Installation by Rick Frausto

June 3 – June 23, 2006

www.myspace.com/rickfraustoart

Questioning the integrity of our current energy policies and the ethics of today’s unsustainable American way of life, Oil Elastic-World of Plastic awakens the dormant consciousness of an American consumed with consumption, confronting an impending global calamity escapable through revolutionary activism or worse: by fate of extraterrestrial divinity. Artist Rick Frausto creates a tribute installation dedicated to the research of activist Charles Moore, founder of the Algalita Marine Research Foundation.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Education Room

On Paper

June 3 – June 18, 2006

An exclusive sale of unique and rare prints, etchings and drawings on paper.

Featuring prominent contemporary artists including SHAG, Sandow Birk, Elizabeth Turk, Rosemary Covey, James Lorigan and more.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Education Room

Friends and Family

May 6 – May 31, 2006

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Main Gallery

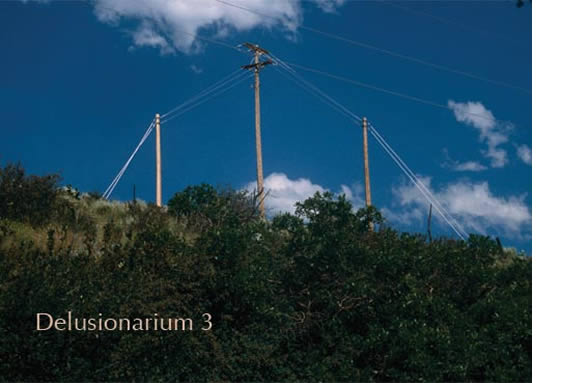

Delusionarium 3

Organized by Jesse Benson

April 1 – May 21, 2006

20 artists address in the 3rd installation in a series of nomadic group exhibitions: Marya Alford, Kathryn Andrews, Andrew Armstrong, Steven Bankhead, Eric Allan Bene, Will Benedict, Jesse Benson, Lindsay Brant, Doug Buis, Tami Demaree, Ed Gomez, Luis G. Hernandez, Matt MacFarland, Jacob Melchi, Tom Norris, Nicole Quaid, Mark Roeder, Joe Sola, Johan Thurfjell and Sam Watters.

The Delusionarium series, organized by Los Angeles-based artist Jesse Benson, was initiated in 2004 as a means of challenging some existing exhibition conditions and certain curatorial agendas.

Each exhibition in the Delusionarium series attempts to form a symbiotic relationship between the work in the show, the exhibition topic, and the situation and space. The Delusionarium series questions the nature of curatorial projects that overwhelm artists’ projects. The series is equally suspect of art objects or art-viewing spaces that act autonomous. The nomadic nature of the Delusionarium series allows each show to take on the specific characteristics of the surrounding space and situation. This makes it more difficult to ignore the conditions of the site, both for the artists and for the viewers. However, the Delusionarium series never asks artists for site-specific projects, as such, merely an awareness of the surrounding conditions.

Most contemporary group exhibitions are dominated by 1 of 3 aspects: 1. artwork that acts autonomous; 2. a curatorial theme that projects too much meaning onto the artwork; or 3. a space that overshadows the projects. The Delusionarium series attempts to find a sort of balance, a symbiosis, between artwork, exhibition topic, and space; Each one is acknowledged by both artist and viewer, without any one aspect dominating. All three factors should work together to provide the most meaningful viewing experience possible, not fight against one another for dominance.

For this reason, Delusionarium 1 and 2 shows explore the huge and open topic of The Romantic. Loaded with potential meanings and aesthetic conversations, the topic of The Romantic is such a broad idea that it allows for a great range of responses from the artists. Though there are occasional links in sensibility and/or in form between projects, each Delusionarium artist poses his/her own specific relationship to the topic and to the conditions of the site. Subject matter, materials, and methodology all range widely amongst the artists in Delusionarium. As for their relationships to The Romantic, artists pose positions that are sometimes cynical, sometimes hopeful, or both.

Delusionarium 3, an exploration of The Romantic and culmination of Delusionarium 1 and 2 includes all types of forms and materials, from installation-based works, to performance, to drawing and painting, to sculpture, kinetic sculpture, and video. Among the projects installed are: a performance and installation using hired female escorts by artist Joe Sola; an interactive video game project by artist Johan Thurfjell; and a sculpture by artist Lindsay Brant based on Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem Ozymandias.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Education Room

Mischief and Delight

April 1 – April 29, 2006

Featuring artists: Amanda Chakravarty, Carolyn Fernandez and Leigh White.

Ceramics by Unjoo Chang

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

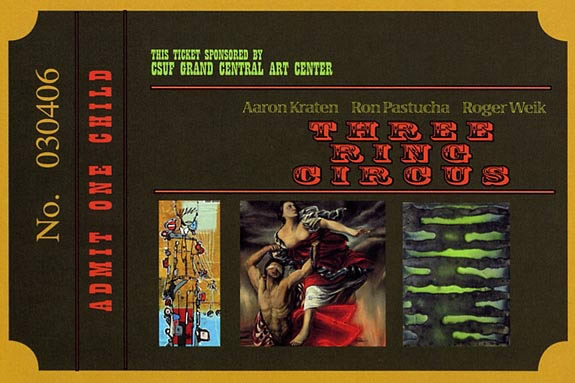

Education Room

Three Ring Circus

March 4 – March 26, 2006

Featuring Aaron Kraten, Ron Pastucha and Roger Weik.

Special Guest Mike Boyle of KUCI “Dryertron” Performance.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Main Gallery

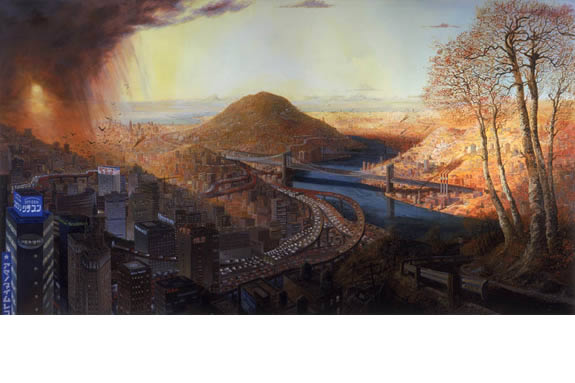

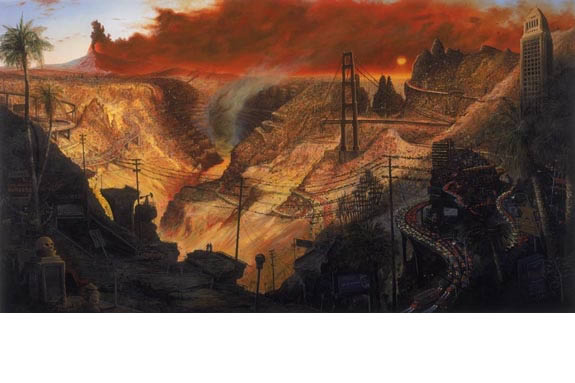

Sandow Birk’s Divine Comedy

Traveling exhibition from San Jose Museum of Art

February 4 – March 20, 2006

Nearly eight hundred years have passed since the Italian poet Dante Alighieri wrote The Divine Comedy-an epic tale that is considered one of Western culture’s greatest literary achievements. Dante’s foretelling journey through the afterlife, with visits to Hell (Inferno), Purgatory (Purgatorio), and Paradise (Paradiso), captivated his medieval readers with vivid descriptions of known public figures in places that before had only been imagined. In 2002, Southern California painter and surfer Sandow Birk decided that The Divine Comedy might be modernized for our own era. Working with Marcus Sanders, a San Francisco writer and contributing editor of Surfing magazine, the pair set about on the enormous task of adapting the text and illustrating the entire story. The result is a deadpan satire of contemporary society from a particularly American perspective that is at once funny, wistful, and sobering.

What was it about The Divine Comedy that attracted Birk to the medieval epic? Perhaps, according to Dante scholar Michael Meister, it was because “Dante asks the big questions: Where are we going? Where have we been? Why is our world such a mess?” Birk, through his series of paintings and prints, takes us on his personal tour of modern metropolises, where police helicopters hover over clogged freeways, fast food joints and used car lots choke crumbling neighborhoods, and corporate logos dot the downtown skylines. From the dark depths of Hell to the hopeful realm of Purgatory and the ethereal heights of Paradise–set against a pastiche of Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York, as well as other cities-Birk’s Divine Comedy reminds us that the choices we make in life are likely to have eternal consequences.

“Sandow Birk’s Divine Comedy” was organized by the San Jose Museum of Art.

CSUF Main Art Gallery and CSUF Grand Central Art Center our extremely honored to be hosting this exhibition on both spaces.

Because of the size of the exhibition (13 large-scale oil paintings and 54 lithographs) this exhibition had to be split between the two venues. The Puragorio and the Paradiso Sections will be at CSUF Main Art Gallery and the Inferno Section will be at CSUF Grand Central Art Center.

Books will be available for sale at the Grand Central Art Center.

Economist.com City Guide, San Francisco: Catch if you can November 2005

Sandow Birk’s Divine Comedy

San Jose Museum of Art

Sandow Birk Goes to Hell

February 22, 2006

by Rebecca Schoenkopf

SANDOW BIRK

March 4 – April 15, 2006 at Koplin Del Rio Gallery, West Hollywood

and February 4 – March 10, 2006 at CSU Fullerton Art Gallery, Orange County

and February 4 – March 20, 2006 at CSUF Grand Central Art Center, Orange County

by Jody Zellen

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Education Room

Neon ! Gas and Glass or A$$

featured artists: Jason Chakravarty, Mike Goodwin, Ryan Ross

February 4 – February 28, 2006

These three artists explore a myriad of thought provoking issues that critic contemporary culture thru the medium of neon lighting and mix media sculpture. The art works in this exhibition also explore the multi faceted dimension of neon gas as a vehicle of expression pushed into new territories of artistic expression.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Education Room

Photographicalilicious

Contemporary photography with artists: Amy Caterina, Scott Angus and Marya Alford

February 3 – February 28, 2006

Photographicalilicious features the artworks of photographers Marya Alford, Scott Angus and Amy Caterina. Marya Alford intertwines literary quotes from classic novels in brail with intriguing subject matter. Scott Angus implies emotional interests to issues of identity and sexuality as life markers. Amy Caterina uses food display as metaphor to examine personal and social exchange.

Collectively, these three artists examine types of social exchange as they appeal to the senses. Photographicalilicious points to a cultivation of photographic imagery that begs for exploration.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •